The increase in extreme weather events is the erratic, sharp end of climate change. But what happens when extreme weather hits the continent of extremes – Antarctica?

Climate scientists Dr Louise Sime and Dr Tom Bracegirdle from British Antarctic Survey are here with your briefing why global warming is causing extreme weather. What does this mean for our future climate? And what are scientists doing to accelerate our understanding of these extreme weather events?

|

Dr Louise Sime, Earth System Modeller | |

|

Dr Tom Bracegirdle, Atmospheric Climate Scientist |

From the record-breaking heatwave in Northern India, to the intense flooding in Dubai, you may feel that you’re seeing more and more coverage of extreme weather and ‘record-breaking’ events in the media.

This isn’t just a media trend: it is an established scientific fact that raised average global temperatures have already led to increasingly severe weather extremes.

When we talk about global warming, the headline average temperature increases of 1.5°C, or 3°C, or more, across our climate system can seem like a relatively modest shift. After all, the average day at the British Antarctic Survey HQ in Cambridge can swing through these temperature ranges in a few hours. However, these averages are the changing context in which we can measure, model and compare the frequency and intensity of extreme events affecting all parts of the globe due to human-induced global warming.

While these changes are particularly well evidenced for temperature, a severe weather extreme can also be a particularly strong storm or hurricane, heavy rainfall or flooding, or drought. In basic terms, this is because warmer air has an increased capacity to hold moisture, which leads to a general increase in severity of precipitation extremes.

(If you want to dive into this in more detail, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report from 2021 is very comprehensive – Chapter 11 is specifically about Weather and Climate Extreme Events.)

These increasing extremes affect every part of our planet… so, of course, at British Antarctic Survey we are interested in what changes we can see in the polar regions and the feedback effect that will have elsewhere.

Extreme weather looks different in extreme places

Antarctica is generally perceived as a region of extremes – but for the plants, animals and delicately balanced ice physical systems, those generally cold, windy and snowy conditions are completely normal. However, in recent years, high impact and record-shattering extreme events have been observed over Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. To the casual observer, this might not be obvious: conditions typical of an average winter’s day in the UK are major extremes for the Antarctic environment.

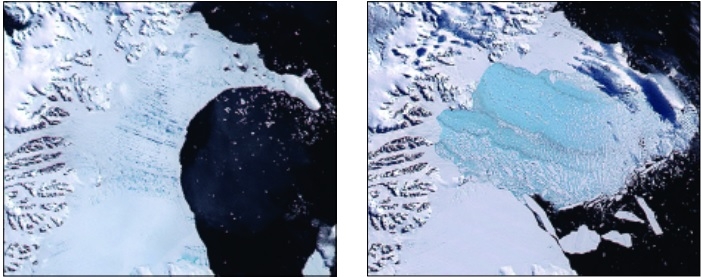

Weather events may be temporary, but they can have a dramatic physical impact. We have examples of this as far back as 2002 when the northern Antarctic Peninsula experienced an extremely warm summer. This caused severe melting over the surface of the Larsen B Ice Shelf, and this melting was implicated in the dramatic breakup of the ice shelf over the course of just a few days in March 2002. Moreover, the disappearance of the ice shelf has since caused the acceleration of the land ice flowing out into the ocean.

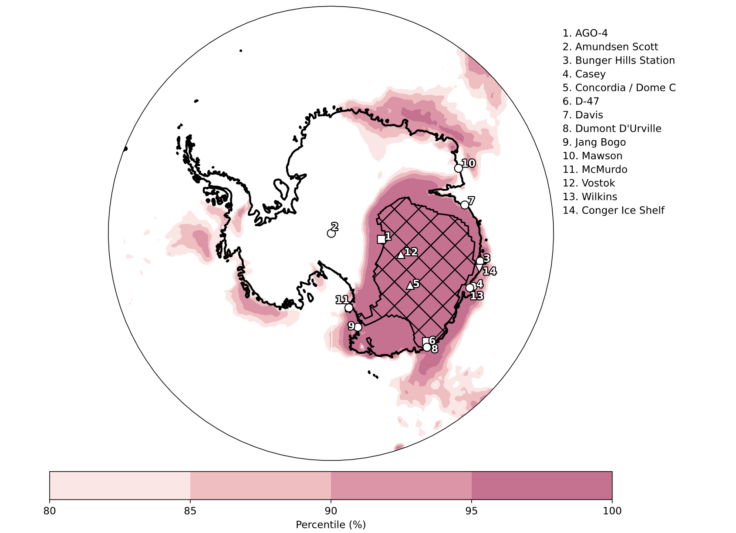

A decade later, and on the high, cold plateaus of East Antarctica, the most extreme heatwave recorded anywhere in the world saw temperatures to rise by 38.5°C above the local average. It was caused by a long, narrow filament of warm and moist air from the tropics moving unusually far poleward, bringing extreme precipitation and relative warmth all the way to Antarctica – a phenomena known as an atmospheric river. The vast amount of moisture led to extreme precipitation over the Antarctic, most of which fell as snow. Counterintuitively, this meant that the heatwave actually added to the overall mass of the sheet.

Weather also has a complicated influence on the formation and breakup of sea ice – the halo of frozen ocean around Antarctica that fluctuates with the seasons. As the last 8 years have seen a consistent decline in sea ice formation in Antarctica, scientists are working to explore a connection. Throughout 2023 the amount of sea ice around Antarctica was at a record low since reliable satellite records began in 1979.

Why does it matter?

Antarctica’s weather may seem very far removed from our daily lives, but what happens there affects all of us. Antarctica’s vast ice sheets are part of the Earth’s delicately balanced global climate systems, and factors that upset this balance have knock-on impacts everywhere.

The obvious impact of rising temperatures is melting ice, which will have a significant effect on global sea level. In West Antarctica, where the impact of warming is already causing visible changes, the ice sheet contains enough water to raise global sea levels by around 3.5 m if it were all to melt, with serious consequences for coastal communities around the world. Predicting the rate of sea-level rise will be crucial for our adaptation.

But it’s not just about rising sea levels. Sea ice is deeply connected to Antarctica’s ecosystems and charismatic creatures like penguins, seals, and whales. They all rely on the ice for their survival, either as habitats or as the start of the Antarctic food chain for smaller creatures like Antarctic krill and salps. Weather extremes can cause the ice to rapidly grow or disappear, exacerbating the effects of a warming ocean, which could cause massive disruption to this unique ecosystem. Moreover, these same creatures contribute to managing carbon in our atmosphere by feeding on sea ice algae blooms, before sinking and sequestering carbon deep in our oceans.

What can we expect in the future?

We are now living through the future that was predicted by previous generations of climate models.

As we look ahead, climate modelling predicts that the recent record-breaking extreme events are relatively minor compared to could be in store under scenarios of increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Under these scenarios, the global impacts of usual weather in Antarctica will only increase as the delicate balance of the system is disturbed more and more often by conditions never seen before.

We need to deepen our understanding of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, and the impacts of extreme weather add a further layer of complexity to this scientific puzzle. By understanding and addressing the challenges posed by Antarctica’s weather, we stand the best chance of helping to protect our planet for future generations.

Research at BAS addressing the issue of extreme events

The British Antarctic Survey is at the forefront of research on extreme weather events over Antarctic and their impacts. We’re leading a number of international projects using the latest technology to retrieve observations of unprecedented detail and use some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers to predict what may happen in the future:

BAS is leading a new research project on drivers and impacts of extreme weather events in Antarctica (ExtAnt – extant.ac.uk). This will unravel the complex causes of Antarctic extremes to gain insight into their changes and impacts both now and into the future.

Meanwhile SURFEIT (surfeit.ac.uk) is a large BAS led project which brings together members of the international scientific community to look closely at how exchange of mass and energy between the surface of the Antarctic ice sheet and the atmosphere impacts sea level rise.