Satellite observations show accelerating greening of Antarctic Peninsula

New research released today in Nature Geoscience reveals that vegetation cover on the Antarctic Peninsula has increased more than tenfold in the past four decades.

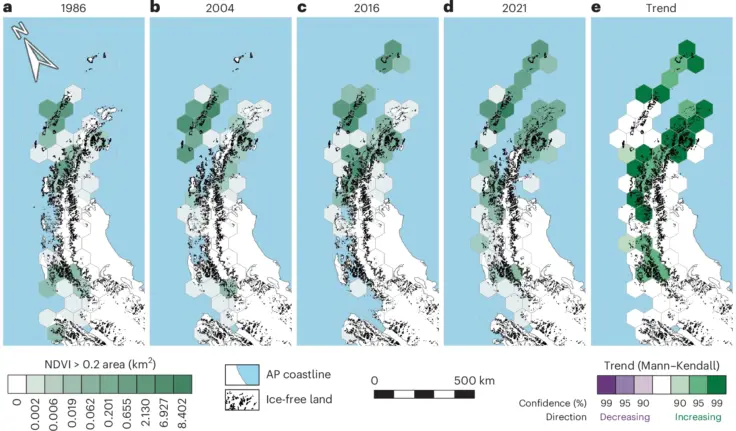

Researchers from University of Exeter, University of Hertfordshire and British Antarctic Survey used satellite data to measure the extent and speed of “greening” occurring in the Antarctic Peninsula as a response to climate change. They found that vegetation cover in the Peninsula rose from less than one square kilometre in 1986, to nearly 12 square kilometres by 2021.

The study also identified an acceleration in this greening trend of over 30% in recent years (2016-2021) compared to the overall study period (1986-2021) – with an annual increase of more than 400,000m2 during this timeframe.

The Antarctic Peninsula is warming at a rate that exceeds the global average, with extreme heat events becoming increasingly frequent in the region.

In earlier research involving core samples from moss-dominated ecosystems on the Antarctic Peninsula, the team found significant evidence of heightened plant growth rates in recent decades. This new study corroborates the widespread greening trend across the Antarctic Peninsula, showing that it is both occurring and accelerating.

Dr Thomas Roland, an environmental scientist from from University of Exeter, said:

“The plants on the Antarctic Peninsula – mostly mosses – grow in perhaps the harshest conditions on Earth. The landscape is still almost entirely dominated by snow, ice and rock, with only a tiny fraction colonised by plant life. But that tiny fraction has grown dramatically – showing that even this vast and isolated ‘wilderness’ is being affected by anthropogenic climate change.”

The research suggests that it is likely that the extent of greening in Antarctica will continue to increase, as emerging ecosystems grow and become more established, and the climate warms.

Dr Olly Bartlett, from the University of Hertfordshire, added:

“Soil in Antarctica is mostly poor or non-existent, but this increase in plant life will add organic matter, and facilitate soil formation – potentially paving the way for other plants to grow. This raises the risk of non-native and invasive species arriving, possibly carried by tourists, scientists or other visitors to the continent.”

The researchers emphasise the urgent need for further research to establish the specific climate and environmental mechanisms that are driving the “greening” trend.

Dr Roland added:

“Our findings raise serious concerns about the environmental future of the Antarctic Peninsula, and of the continent as a whole. In order to protect Antarctica, we must understand these changes and identify precisely what is causing them.”

The researchers are currently exploring how newly deglaciated landscapes are being coloniSed by plants and how this process may evolve in the future.

“Sustained greening of the Antarctic Peninsula observed from satellites”

by Thomas P. Roland, Oliver T. Bartlett, Dan J. Charman, Karen Anderson, Dominic A. Hodgson, Matthew J. Amesbury, Ilya Maclean, Peter T. Fretwell & Andrew Fleming is published today in Nature Geoscience.