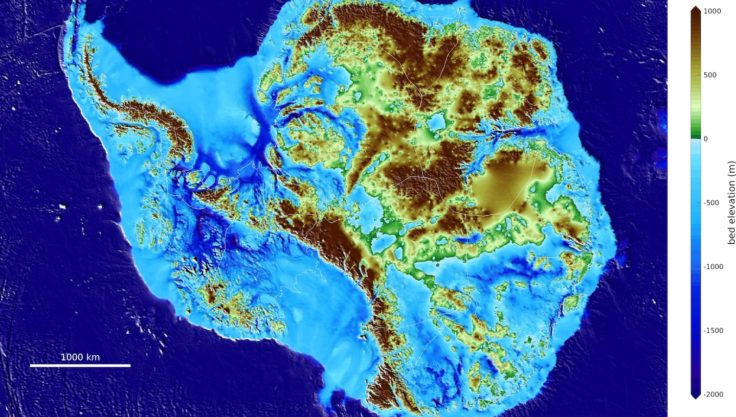

New high-precision map of Antarctica’s bed topography

A team of glaciologists has unveiled the most accurate portrait yet of the contours of the land beneath Antarctica’s ice sheet – and, by doing so, has helped identify which regions of the continent are going to be more, or less, vulnerable to future climate warming.

Highly anticipated by the global cryosphere and environmental science communities, the newly released Antarctica topography map, BedMachine, and related findings were published today (12 December 2019) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Among the most striking results of the BedMachine project are the discovery of stabilizing ridges that protect the ice flowing across the Transantarctic Mountains; a bed geometry that increases the risk of rapid ice retreat in the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers sector of West Antarctica; a bed under the Recovery and Support Force glaciers that is hundreds of meters deeper than previously thought, making those ice sheets more susceptible to retreat; and the world’s deepest land canyon below Denman Glacier in East Antarctica.

“There were lots of surprises around the continent, especially in regions that had not been previously mapped in great detail with radar,” says lead author Mathieu Morlighem, associate professor of Earth system science at University of California Irvine.

“Ultimately, BedMachine Antarctica presents a mixed picture: Ice streams in some areas are relatively well-protected by their underlying ground features, while others on retrograde beds are shown to be more at risk from potential marine ice sheet instability.”

The new Antarctic bed topography product was constructed using ice thickness data from 19 different research institutes dating back to 1967, encompassing nearly a million line-miles of radar soundings. In addition, BedMachine’s creators utilized ice shelf bathymetry measurements from NASA’s Operation IceBridge campaigns, as well as seismic information, where available.

“Using BedMachine to zoom into particular sectors of Antarctica, you find essential details such as bumps and hollows beneath the ice that may accelerate, slow down or even temporarily stop the retreat of glaciers,” Morlighem said.

Previous Antarctica mapping methods relying on radar soundings have been generally effective, with some limitations. As aircraft fly in a straight line over a region, wing-mounted radar systems emit a signal that penetrates the ice and bounces back from the point at which the ice meets solid ground. Glaciologists then use interpolation techniques to fill in the areas between the flight tracks, but this has proven to be an incomplete approach, especially with fast-flowing glaciers.

Alternatively, BedMachine relies on the fundamental physics-based method of mass conservation to estimate what lies between the radar sounding lines, utilizing highly detailed information on ice flow motion from satellite data that dictates how ice moves around the varied contours of the bed. This technique was instrumental in the research team’s conclusion regarding the true depth of the Denman trough.

“Older maps suggested a shallower canyon, but that wasn’t possible; something was missing,” Morlighem said. “With conservation of mass, by combining existing radar survey and ice motion data, we know how much flows through the canyon – which, by our calculations, reaches 3,500 meters below sea level, the deepest point on land. Since it’s relatively narrow, it has to be deep to allow that much ice mass to reach the coast.”

By basing its results on ice surface velocity in addition to ice thickness data from radar soundings, BedMachine is able to present a more accurate, high-resolution depiction of the bed topography. This methodology has been successfully employed in Greenland in recent years, transforming cryosphere researchers’ understanding of ice dynamics, ocean circulation and the mechanisms of glacier retreat.

Applying the same technique to Antarctica is especially challenging due to the continent’s size and remoteness, but, Morlighem noted, BedMachine will help reduce the uncertainty in sea level rise projections from numerical models.

Dr Peter Fretwell from British Antarctic Survey is a co-author. He says:

“One of the main advances in this new map of the bed beneath the Antarctica is the inclusion of new topography around the coast, especially in a number of important glacial outflows.

“The surface above these fast flowing outflow channels is often crevassed and radio-echo sounding, the traditional method of surveying the bed, struggles to get a clear picture of what’s beneath them. This new map uses physics driven modelled output to re-map these channels. The outflow channels are often very deep and therefore, when they meet the sea, they often come into contact with warm seawater that exists below the cold surface layers. This is thought to be one of the key drivers of ice melt in Antarctica. Knowing the geometry and topographic of these deep channels will give ice sheet modelers critical clues to how Antarctic ice sheets will react to predicted future climate change.”

The BedMachine Antarctica project was supported by NASA’s Cryospheric Sciences Program, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Australian government’s Cooperative Research Centres Programme and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, with participation from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Alfred Wegener Institute, the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, British Antarctic Survey, the Technical University of Denmark, Northumbria University, the Polar Research Institute of China, The Ohio State University, the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, the Korea Polar Research Institute, the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research at Utrecht University, the Norwegian Polar Institute, Grenoble Alps University, the NSF’s Center for Remote Sensing of Ice Sheets, the Université Libre de Bruxelles and the Australian Antarctic Division.

BedMachine Antarctica is publicly available through the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.