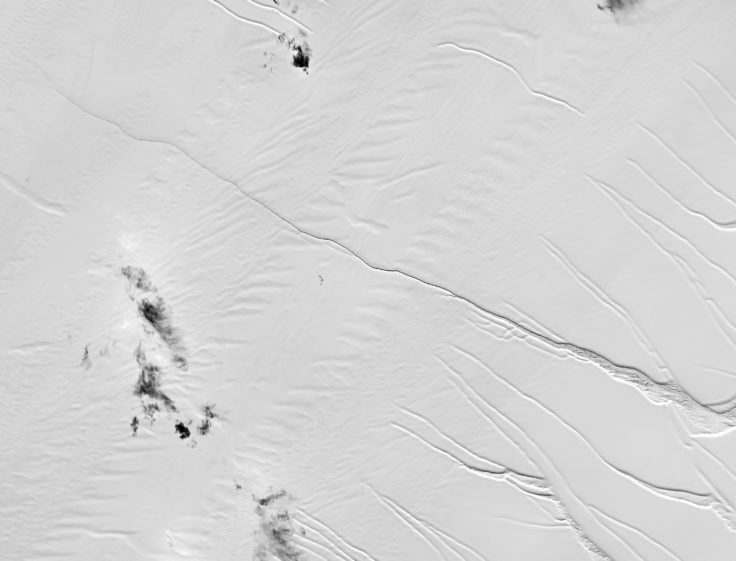

A huge iceberg, roughly the size of Norfolk, looks set to break away from the Larsen C ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula. Larsen C is more than twice the size of Wales. Satellite observations from December 2016 show a growing crack in the ice shelf which suggests that an iceberg with an area of up to 5,000 km² is likely to calve soon.

Researchers from the UK-based MIDAS project, led by Swansea University, have reported several rapid elongations of the rift in recent years. British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists are involved in long-running research programme to monitor ice shelves from both above and below to understand the causes and implications of the rapid changes observed in the region. BAS is also monitoring the rift for operational reasons.

During the current Antarctic field season, a glaciology research team has been on Larsen C using seismic techniques to survey the seafloor beneath the ice shelf. Because a break up looks likely the team has not set up camp on the ice as usual. Instead they have made field trips by twin otter aircraft supported from Rothera Research Station.

Ice shelves in normal situations produce an iceberg every few decades. There is not enough information to know whether the expected calving event on Larsen C is an effect of climate change or not, although there is good scientific evidence that climate change has caused thinning of the ice shelf. Once the iceberg has calved the big question is whether the entire ice sheet may collapse. This is something that British Antarctic Survey teams have been monitoring and why glaciologists were deployed to work on Larsen C in the past few weeks.

Glaciologist Professor David Vaughan OBE, Director of Science at British Antarctic Survey, said,

“The calving of this large iceberg could be the first step of the collapse of Larsen C ice shelf, which would result in the disintegration of a huge area of ice into a number of icebergs and smaller fragments.

“Because of the uncertainty surrounding the stability of the Larsen C ice shelf, we chose not to camp on the ice this season. Researchers can now only do day trips from our Rothera Research Station with an aircraft nearby on standby.”

Satellite technology

Dr Andrew Fleming, Remote Sensing Manager at British Antarctic Survey, said,

“We use regular satellite images provided by the European Sentinel satellites to monitor cracks in the ice shelf. These images are perfect for following these changes since they provide detailed information, day or night and regardless of cloud cover.”

About ice shelves

An ice shelf is a floating extension of land-based glaciers which flow into the ocean. Because they already float in the ocean, their melting does not directly contribute to sea-level rise. However, ice shelves act as buttresses holding back glaciers flowing down to the coast. Larsen A and B ice shelves, which were situated further north on the Antarctic Peninsula, collapsed in 1995 and 2002, respectively. This resulted in the dramatic acceleration of glaciers behind them, with larger volumes of ice entering the ocean and contributing to sea-level rise.

The largest icebergs known have all calved from ice shelves. In 1956, a huge iceberg of roughly 32,000 km² – bigger than Belgium – was spotted in the Ross Sea by a US Navy icebreaker. However, since there were no satellites in orbit at this point, its exact size was not verified. In 1986, a section of the Filchner ice shelf roughly the size of Wales calved – but this iceberg broke into three pieces almost immediately. The largest iceberg recorded by satellites calved from the Ross ice shelf in 2001, and was roughly the size of Jamaica at 11,000 km².

The below video shows footage from the breakup of the Wilkins ice shelf, also on the Antarctic Peninsula, in 2008.