Fish survival in the extreme cold

An international team of researchers has sequenced the genomes of 24 Antarctic fish species to investigate how they survive the extreme cold. The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, enables understanding of how these fish organisms survive in the subzero Southern Ocean, and sheds light on the evolutionary history of these iconic fish.

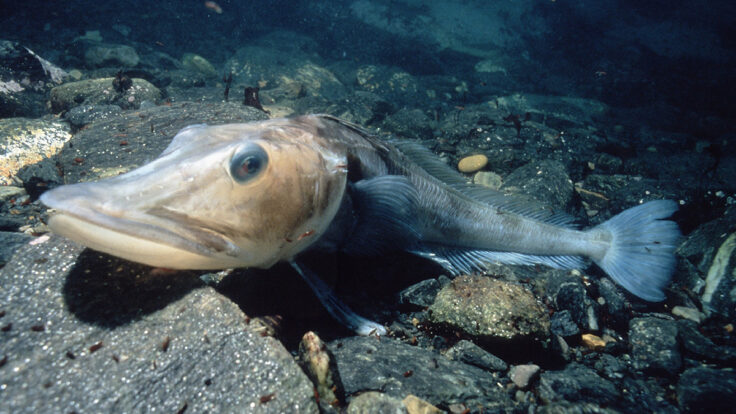

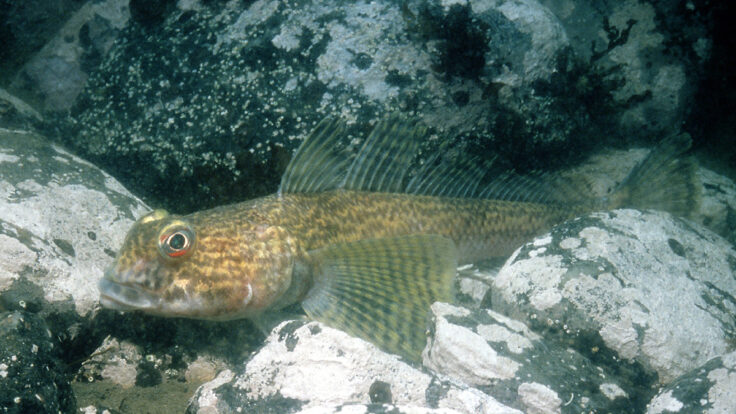

Notothenioids are a unique group of fish species. They live in the cold waters below the sea ice of Antarctica, which is largely isolated from the rest of the marine world by a circular current around the continent. The fish are remarkable in many ways. For example they have evolved antifreeze proteins which allow them to survive the water temperatures, which can reach -2°C (28 F) – a pretty hostile environment for most species. One subgroup of notothenioids – called “icefish” – have lost their oxygen-binding haemoglobin proteins and that makes them the only vertebrates known to not have red blood.

British Antarctic Survey (BAS) researcher Professor Melody Clark is a co-author on the paper. She says:

“This is an amazing achievement. The sequencing of so many Antarctic fish genomes will enable us to make real inroads into identifying how these animals manage to survive in such freezing conditions.”

The international team of researchers from UK, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and the US, have sequenced the genomes of 24 species of notothenioid fish. These new genome data were generated using the latest long-read technologies, which enabled the team to determine the sequence of complex, repetitive regions of DNA in the genome that it has not previously been possible to decipher. Using these new data they explore the evolutionary history of the notothenioids and the mechanisms that support adaptation to extreme cold. They show that the cold-resistant notothenioids split off from other species about 10.7 million years ago, which is more recent than was previously thought, and many new species started evolving rapidly at approximately 5 million years ago.

Several genomic characteristics have aided the survival and establishment of this group. The researchers found that the size of the genome has doubled in the species that specialize in extreme cold, such as the family of Channichthyidae or “icefish”. This expansion of the genome size was due to a large increase in the number of genomic elements known as transposons which have the ability to copy themselves into new positions within the genome and can potentially introduce new functions.

At the same time, functions that are normally considered essential for survival such as the production of haemoglobin, have been lost in the icefish.

Dr Iliana Bista, a geneticist working with Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands and Wellcome Sanger Institute in the UK, and lead author of the paper, says:

“Survival in such a harsh environment requires additional compensations of the organism and these fish have developed special proteins that act as antifreeze to stop them from freezing”.

These fish are the only vertebrates known to have completely lost their haemoglobins, and their blood looks white. This is remarkable because haemoglobins are needed to transport oxygen through the body; their loss in icefish is only possible because oxygen dissolves better in water at very low temperatures, and because of additional genomic and physiological adaptations.

Senior author, Richard Durbin from the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, explains why this sort of research is important:

“Notothenioid fish live at the edge of viability. Sequencing a broad collection of their genomes gives insights into how they have evolved to survive there, and supports our understanding of a critical ecosystem. This study is a great example of how advances in genomics are revolutionizing our ability to understand biodiversity across the world.”

“Genomics of cold adaptations in the Antarctic notothenioid fish radiation”,

by Iliana Bista, Jonathan M. D. Wood, Thomas Desvignes, Shane A. McCarthy, Michael Matschiner, Zemin Ning, Alan Tracey, James Torrance, Ying Sims, William Chow, Michelle Smith, Karen Oliver, Leanne Haggerty, Walter Salzburger, John H. Postlethwait, Kerstin Howe, Melody S. Clark, H. William Detrich III, C.-H. Christina Cheng, Eric A. Miska, and Richard Durbin is published in Nature Communications, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38567-6