Arctic sea ice summer minimum 2014: A scientific perspective

The Arctic sea ice minimum marks the day – typically in September – when sea ice reaches its smallest extent at the end of the summer melt season. The Arctic is an ocean surrounded by land and Arctic sea ice is the thin layer of frozen ocean water that forms and grows during the winter, and melts in the summer.

Dr Jeremy Wilkinson from the British Antarctic Survey provides a scientist’s perspective on the trend for decreasing Arctic sea ice.

Unquestionable Arctic sea ice retreat

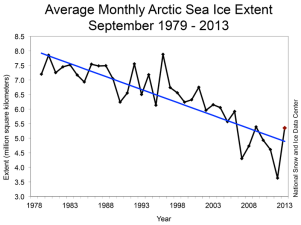

The retreat of summer Arctic sea ice is unquestionable. The use of the word unquestionable is deliberate as for over 35 years special satellite-mounted sensors, which can see through cloud and the polar night, have been continuously obtaining daily ‘images’ of the entire Arctic region. From these Arctic-wide images, the extent of the sea ice can be clearly and accurately determined, day after day and year after year. The resultant time-series shows that we have moved from an average sea ice extent in September of over 7 million km2 in the 1970s to about 3.5 million km2 in 2012; a loss of about half the summer Arctic sea ice cover.

Natural variability

It is important to note that the reduction in Arctic sea ice is not expected to be consistent from one year to the next. For example, a year with smaller ice extent could be followed by a number of years with a significantly larger ice extent. This is Mother Nature in action, and variability is fully expected. With this in mind, the increase in ice extent over the last two years (since the 2012 minimum) is neither unusual nor unexpected. It is the trend (the change over the entire time-series) that is significant; which unquestionably shows a substantial decrease over the time-series (see figure). Importantly, all climate models predict that the extent of the summer Arctic sea ice will continue to retreat over the coming decades; none show an increase.

Arctic change

We have witnessed changes to the Arctic system that only a decade ago would not have been thought possible. These changes have the potential, through complex linkages and feedback mechanisms, to influence all aspects of the Earth system. As a consequence, Arctic change will have a significant impact on the livelihoods of Arctic residents, as well as considerable socio-economic implications at national, regional, and global levels. Whether their net impact is positive or negative is still open to debate. For example, observed changes have already led to greater marine access to previously ice-covered waters and, as a result, we have witnessed an intensification of activities such as fishing, oil and mineral exploration/exploitation, shipping, and tourism. These short-term gains may be offset by the long-term impact of global warming through our increased susceptibility to high-cost natural events such as severe storms, sea level rise, and extensive species loss.

Robust science for robust policy making

Given the global consequences of Arctic change we have to ensure that the public, industry, national and international politicians and policy-makers have the most up-to-date and robust science available on Arctic change. Good policy decisions are based on rigorous scientific analysis. The recent controversy regarding the “increase” in the Arctic summer sea ice extent over the past two summers needs to be placed in context within the time-series available.

Understanding Arctic change

The Arctic is changing and will continue to change. It is clear that we need to better understand Arctic change. This is an exceedingly difficult task as the issues associated with Arctic change transcend national boundaries, sectors, and disciplines. No one nation has the sovereignty, expertise, or budget to individually tackle these challenges head on; a truly international and integrated scientific effort is needed. Through international programmes like the major EU-funded ICE-ARC programme we are developing a better understanding of the fundamental workings of the Arctic system, and the net consequences of these changes to the global economy.

Notes

- Sea ice

- is the thin layer of frozen ocean water that forms and grows during the winter, and melts in the summer.

- Sea ice extent

- is the area of ocean covered by sea ice.

Antarctic and Arctic sea ice science briefing note