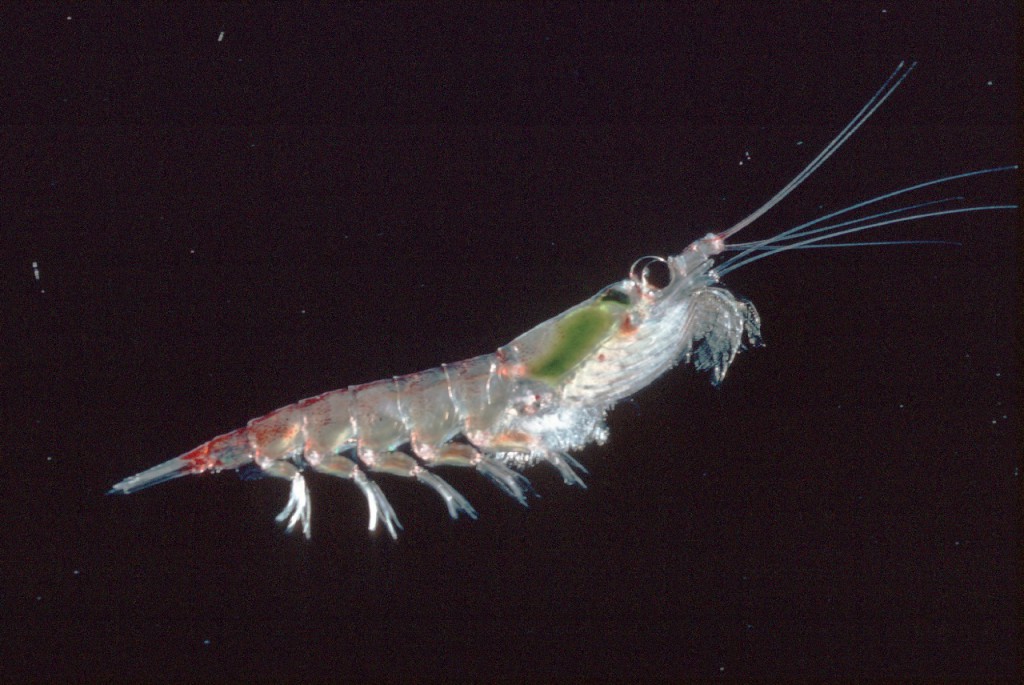

Antarctic krill help to fertilise Southern Ocean with iron

A new discovery reveals that the shrimp-like creature at the heart of the Antarctic food chain could play a key role in fertilising the Southern Ocean with iron — stimulating the growth of phytoplankton (microscopic plant-like organisms). This process enhances the ocean’s capacity for natural storage of carbon dioxide.

Reporting this month in the journal Limnology and Oceanography, an international team of researchers describe how Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), once thought to live mostly in surface waters, regularly feed on iron-rich fragments of decaying organisms on the sea floor. They swim back to the surface with stomachs full of iron, releasing it into the water.

Antarctic krill is the staple diet for fish, penguins, seals and whales, and is harvested by commercial fisheries for human consumption.

Lead author from British Antarctic Survey, Dr Katrin Schmidt says,

“We are really excited to make this discovery because the textbooks state krill live mainly in surface waters. We knew they make occasional visits to the sea floor but these were always thought of as exceptional. What surprises us is how common these visits are — up to 20% of the population can be migrating up and down the water column at any one time.”

The scientists painstakingly examined the stomach contents of over 1000 krill collected from 10 Antarctic research expeditions. They found that the krill, caught near the surface, had stomachs full of iron-rich material from the seabed. The team also studied photographs of krill on the sea floor, acoustic data and net samples. All these provided strong evidence that these animals frequently feed on the sea floor.

This finding has implications for managing commercial krill fisheries and will lead to a better understanding of the natural carbon cycle in the Southern Ocean.

Schmidt continues,

“The next steps are to look at exactly how this iron is released into the water.”

ENDS

Issued by British Antarctic Survey Press Office:

Athena Dinar, Tel: +44 (0)1223 221414; email: amdi@bas.ac.uk; Mobile: +44 07736 921693

Author contacts:

Dr Katrin Schmidt email: kasc@bas.ac.uk

Dr Angus Atkinson tel. +44 (0) 1223 221306; email: aat@bas.ac.uk

This research was carried out by British Antarctic Survey, Southampton University, Australian Antarctic Division and Oslo University.

The paper, Seabed foraging by Antarctic krill: Implications for stock assessment, bentho-pelagic coupling, and the vertical transfer of iron by Katrin Schmidt, Angus Atkinson, Sebastian Steigenberger, Sophie Fielding, Margaret C.M. Lindsay, David W. Pond, Geraint A. Tarling, Thor A. Klevjer, Claire S. Allen, Stephen Nicol and Eric P. Achterberg is published in Limnology and Oceanography. 56: 1310–1318.

Notes for Editors

Photos of krill and scientists collecting samples from the research ship RRS James Clark Ross are available from the British Antarctic Survey Press Office as above.

Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) is one of the most important animals in the Southern Ocean. These shrimp like crustaceans grows up to a length of 6cm and can live for 5–6 years. Krill feed on phytoplankton and are in turn eaten by a wide range of animals including fish, penguins, seals and whales. They are also a potentially valuable source of protein for humans and can be fished easily with large nets.

Antarctic krill are a key species in the Southern Ocean food web, channelling energy from phytoplankton (microscopic plants) efficiently to the large populations of penguins, seals and whales that make Antarctica unique. There is an expanding krill fishery in Antarctica, managed by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). CCAMLR requires research on the role of krill in the wider food web, in order to manage this expanding fishery in a precautionary manner.

There are an estimated 100–500 million tonnes of krill in the Southern Ocean — similar to the weight of the world’s human population.

Primary production (pelagic plant growth) is limited by the availability of iron in about 40% of the Worlds’ Oceans including the Southern Ocean. Whilst iron is super-abundant on land, it is only present in minute concentrations in the upper productive layers of the ocean. In large parts of the Southern Ocean small additions of iron dramatically increase plant growth and the drawdown of atmospheric CO2 into the ocean.

The supply of iron is mainly thought to be due to upwelling from deep sediments, run-off from land and glaciers, melting of icebergs and the settling of wind-blown dust. All of these processes are purely physical, so this work suggests a novel route via biological processes: with krill returning significant quantities of iron in their stomachs after visiting the seafloor to feed.

The Cambridge-based British Antarctic Survey (BAS) is a world leader in research into global environmental issues. With an annual budget of around £45 million, five Antarctic Research Stations, two Royal Research Ships and five aircraft, BAS undertakes an interdisciplinary research programme and plays an active and influential role in Antarctic affairs. BAS has joint research projects with over 40 UK universities and has more than 120 national and international collaborations. It is a component of the Natural Environment Research Council.

The Australian Antarctic Division leads the Australian Government’s Antarctic program and is a division of the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Australia maintains three stations on the Antarctic continent — Mawson, Davis and Casey, and a sub-Antarctic station on Macquarie Island. Remote field bases also operate during the summer research season, supporting coastal, inland and traverse operations. Australia’s icebreaker, RSV Aurora Australis is the platform for a large annual marine research effort focussed on the Southern Ocean and assists in resupplying our research stations. We also operate a jet aircraft link between Hobart and a 3.5 km blue-ice runway near Casey.