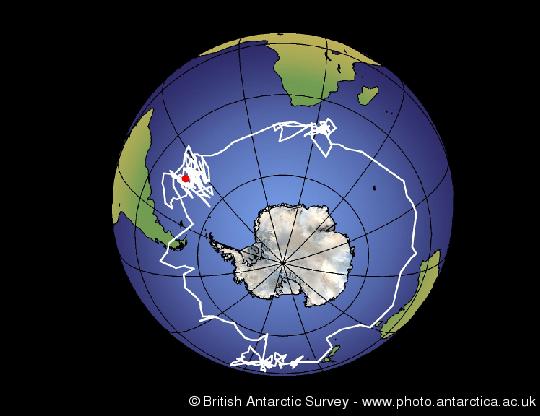

A new study of the movements of sub-Antarctic albatrosses tracked from two remote islands some 5,000 km apart, shows that although the birds from each breeding site take similar routes around the Southern Ocean, they forage in different areas for the majority of the time. The results are published this month in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

Grey-headed albatrosses (Thalassarche chrysostoma) spend up to 16 months at sea between breeding seasons and often circumnavigate the Antarctic continent. During this time, they can cover up to 240,000 km in search of their preferred food: fish, squid and krill.

The team from British Antarctic Survey (BAS), University of Cambridge and University of Cape Town, tracked albatrosses from the sub-Antarctic islands of Bird Island (South Georgia) in the Atlantic Ocean, and Marion Island in the Indian Ocean.

The birds were fitted with tiny geolocators, which record light levels from which their location can be estimated to around 180 km. The researchers developed computer models to identify which environmental factors influence where the birds go. One finding was that individuals from Bird Island visited areas known to be richer in food than their Indian Ocean counterparts. In addition, the researchers found that females often travelled further north than males, which is likely because the males are better able to exploit the stronger winds further south.

Tommy Clay, lead author at BAS, says:

“Albatrosses are perfectly adapted for flying in the windy Southern Ocean environment, and are able to travel massive distances to find food. What we now know is that birds from the Indian Ocean fly directly past foraging areas in the South Atlantic without stopping to feed. We believe they do this to avoid competing with birds from South Georgia, the world’s largest breeding population. Through this study we have a much better understanding of the factors influencing these impressive migrations, and how birds from different populations coexist.”

Dr Richard Phillips, author and seabird ecologist at BAS says:

“The conservation status of grey-headed albatrosses has recently been upgraded to ‘Endangered’, due to the impacts of environmental change and fisheries, so it is essential that we understand their distribution and behaviour at sea. While the Bird Island population is in rapid decline, the Marion Island population appears to be stable. The knowledge that birds from different populations use different areas enables us to better assess the nature and the extent of the threats that they face.”

Read the paper here