SHIP BLOG: Lost in a Sea of Biology

16 March, 2016 RRS James Clark Ross

Lost in a Sea of Biology!

Dr Laura Robinson is interested in documenting and understanding the processes that govern climate on time scales ranging from the modern day back through hundreds of thousands of years. She is a member of the SO-AntEco research cruise onboard the RRS James Clark Ross. She’s working with an international team of scientists from the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR) AntEco research programme.

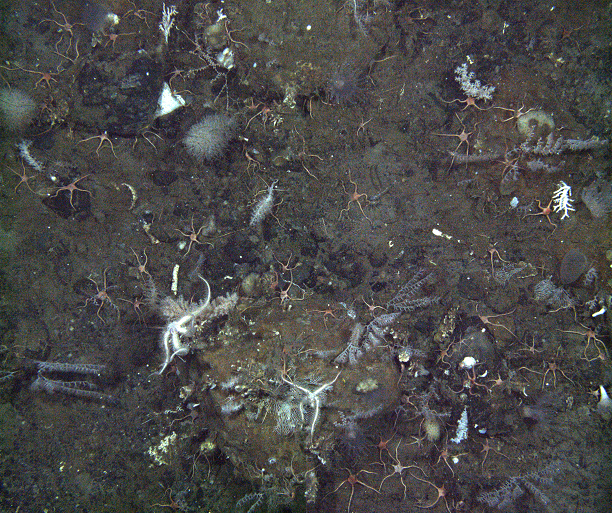

I’ve been to sea a few times now, it’s coming up to having spent the best part of a year far from home on various floating laboratories. I was invited on this expedition because I work on deep-sea corals – thinking about where they live, and why, as well as using their skeletons to reconstruct ocean history. With our camera system and collections we have been able to see and collect corals from depths as great as 1.6km below the seasurface. However, on this trip I have been racking up new experiences every day, as I help the biology-focused team with their work.

So why do I feel lost in a sea of biology when it sounds like I should know what is going on? I have certainly been out on voyages with biologists, I have even lead a trip collecting deep sea samples…but normally the biology specialists quickly sort and separate their samples and disappear to work with their samples. But now I know what they are doing, and I can let you in on some of their secrets…

Collecting deep sea samples

I’ll take an example of our ‘AGT’ sampling. The AGT , or Agassiz trawl, is a type of research trawl that can collect samples from the seafloor if you tow it behind the ship at a set distance. Once it comes up on to deck everyone gathers around with buckets and trays to see what we have collected. If it is muddy then we break out the seawater hoses, if not we quickly bring the specimens in to the lab for sorting. In the past I have enthusiastically picked up the rocks, and the hard skeletons and shells of organisms so that I can analyse the chemistry and find out how they make their hard body parts and what they can tell us about the past ocean. Here everyone jumps on the ‘soft’ samples – we work fast and gently to preserve the animals as well as we can. It isn’t as easy as it sounds if they ship is rocking, and we are wearing full on outdoor gear with big gloves and small tweezers.

The samples come into the first ‘wet’ lab and the feelings of being a geologist out of her depth begin… with great glee someone shouts ‘ascidian’, ‘salp’ or ‘ holothurian’ whilst I mutter ‘green blob’. I am learning fast… the holothurian is also called a sea cucumber – it is related to a sea urchin and a starfish, it should not be confused with a sea slug, barnacles are more closely related to crabs than to limpets… they may look to the same to an untrained eye, but the fantastic crew of experts aboard can tell at a glance. And I am quickly getting my eye in – I have the salps (gelatinous blobs), I can do the holothurians (except the small ones that look like worms) I can even tell my hairy sea spiders from the smooth ones. But who cares? Well, we all should. We may be a long way from home, and it may be the bottom of the seafloor but this is an important part of the global ecosystem – the food comes from the productive surface waters, corals and sponges form habitats for international fisheries, deep sea organisms can provide new natural products… all areas of focus for those on board. Just as important it to actually find out what lives where, and why – within a single trawl we can find new species – we simply don’t know what lives out here, and you need to be an expert in that group of animals to know if it is new.

Let’s get sorted

Back to the sorting – what do we do when we have the animals roughly sorted – they need a number, so we have an accurate record of where they were collected – then we go into sample overdrive… a photograph first.. .then a series of special procedures for each animal. Some must go into formalin to preserve their internal organs, some go in ethanol so that they are preserved for DNA extraction, some are frozen – and we have to get each one correct. My absolute favourite is the protocol for anemones, and I volunteer every time – they must be relaxed… but how on earth to relax a sea anemone? The protocol says to place it in an individual aquarium on a bed of black velvet, add menthol crystals and put it in the fridge. What? What? Yes – we are relaxing anemones – and there is a good reason. When they are closed up (like at low tide on a beach rock pool) you can’t identify them very easily, you need to see their tentacles. So we have to encourage them to open up, hence the special treatment. The bed of velvet is really so that it is easy to photograph once it is open. I must confess my efforts have not yet been properly rewarded, but I hope by the end to tempt my first anemone out of hiding (note, at time of publication I have now succeeded!)

On to my battle with a deep-sea leach – I had no idea that leaches lived in the deep sea – they are related to earth worms….this particular leach was very active, and kept crawling out of his petri dish and across the lab bench when I wasn’t looking. My efforts to pick him up with the tweezers was a challenge – we all know that leaches like to suck, and this one was no different – he kept sticking to anything available, the dish, the bench the tweezers… it was a challenge… at last I managed to capture him, and he has been preserved for identification by colleagues back in Europe. Whilst it is exciting to capture a rare organisms, I cannot pretend to be looking forward to my next leach experience, I might stick with the shrimps….

So here I am on a day we are making maps using on board mapping equipment to help us define habitat types. I have a little time to reflect on what I have learnt, and it is a great deal. I feel more confident to shout out ‘salp’ with the rest of the group, and I appreciate what great work taxonomists and museums do in curating the extent of the natural world.

NB: My role on the boat is to collect calcium carbonates shells of marine organisms, particularly corals. My research group at the University of Bristol uses these shells to reconstruct the history of the Southern Ocean. Check out this talk for more information: http://www.ted.com/talks/laura_robinson_the_secrets_i_find_on_the_mysterious_ocean_floor