SCIENCE ON THE ICE: 20th visit to Antarctica

12 January, 2018 Halley

It’s been over 30 years since British Antarctic Survey meteorologist Jonathan Shanklin first visited at Halley Research Station. He’s one of few who has spent 20 Antarctic seasons living and working on the ice and was part of the trio who made the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer in 1985, which led to a global ban of ozone depleting chemicals.

He returns to Antarctica this season as a meteorological observer at Halley Station on the Brunt Ice Shelf. On this trip he explains his role at Halley and how it feels to be back 36 years after his first visit in 1982.

Arriving back at Halley I was greeted by a familiar sight, although the station is now in a different location to the last time I was here.

My first full day at Halley was spent undertaking a range of training modules including communication, clothing, medical, field kit and skidoo use. I also took the opportunity to walk to the Meteorology hut (Met Caboose), the Balloon Launching Platform (BART) and the Automatic Weather Station. These facilities are essential for my role as a meteorological observer. BAS has been monitoring and collecting meteorological and ozone data here since the 1950s?, which feeds into the Met Office’s global weather forecasting system.

The next day I arrived at the Met Caboose at 7 am to begin my work. My main responsibilities include making regular surface weather observations – hourly observations of the visibility and the amount, type and height of clouds – for aircraft operations, forecasting and climate studies and launching weather balloons.

My first task was to provide observations estimating the visibility and the amount, type and height of clouds for an incoming flight bringing BAS to Halley. These have to be made every hour until the plane has landed. We had to continue to provide hourly observation after the aircraft had departed, until it was half-way to the German Neumayer station.

Later in the morning we launched a weather balloon, which ascended to 27 km, measuring temperature, pressure and humidity via a radiosonde. Wind speed and direction are also calculated using a GPS.

At intervals ozone observations were made using “Daphne” the Dobson ozone spectrophotometer (No 31), which is around 60 years old, and still one of the world standard instruments for measuring ozone. The electronics have been updated over the years, but the mechanics are largely the same as when it was built.

These three tasks form the basis of my daily routine, however, the launching of weather balloons and ozone measurements are highly dependent on the weather conditions.

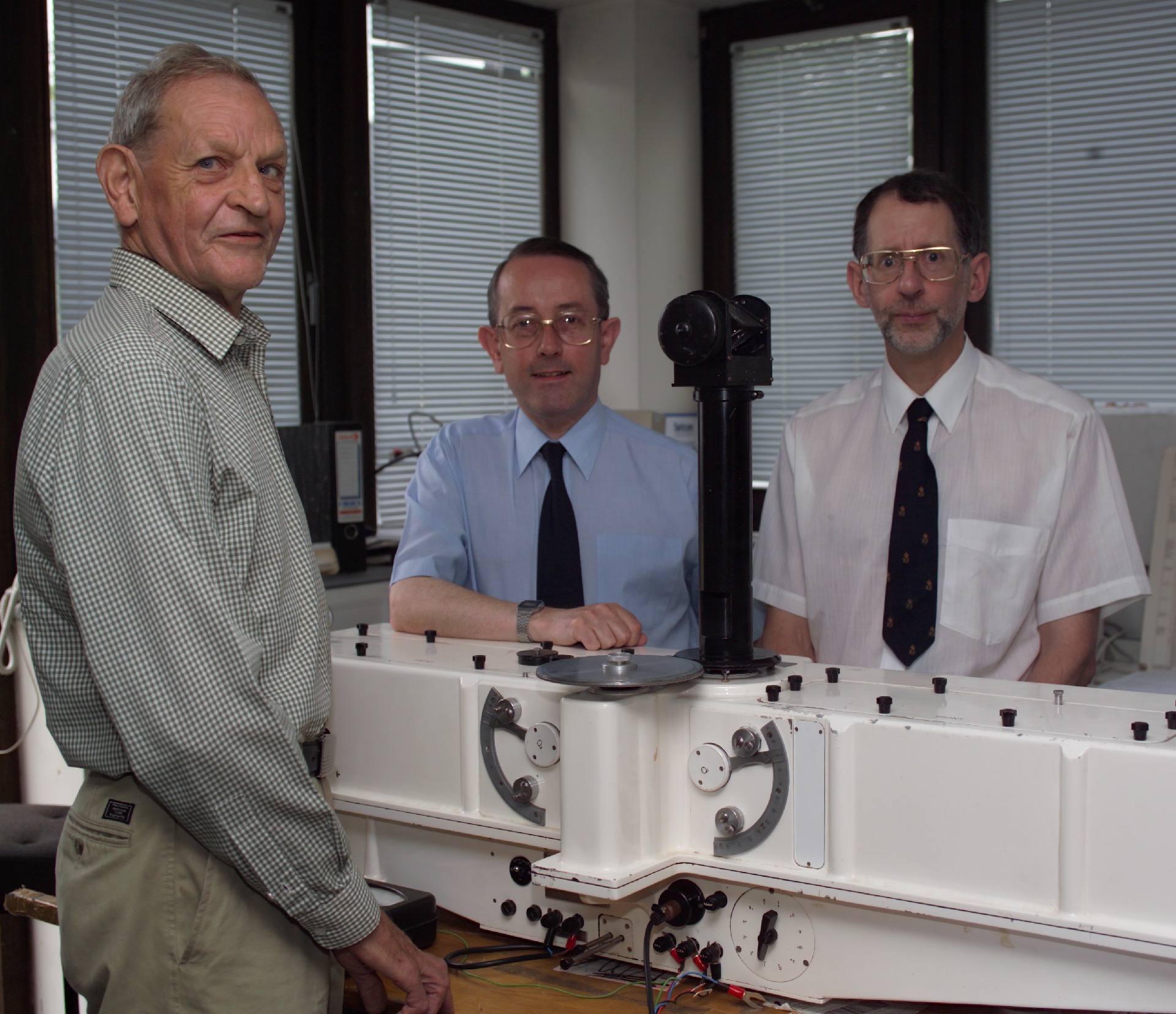

One of the most exciting tasks so far has been starting “Daisy” the newer Dobson spectrophotometer (No 73) that we hope will run unattended over the winter. It reminded me of my first visit to Halley when I was involved in installing and operating Dobson 123 outside on the snow surface. Atmospheric ozone measurements from Halley led to the discovery of the ozone hole by myself, Joe Farman and Brian Gardiner from British Antarctic Survey in 1985.

Daisy was brought out of the aluminium trunk in which she had been transported from the UK and put on the packing case in which Daphne had spent the winter. A power lead was plugged into the met caboose, and the motor in Daisy started to turn. After a few tests it seemed that she had more or less retained the calibration that had been made the previous summer at Hoenpeissenberg in Germany and at Cambridge.

Since this success, along with my usual routine I have been doing lots of calibration measurements on Daisy and Daphne.