SCIENCE IN THE SEA – Part 3: Gliders galore!

20 December, 2017 RRS James Clark Ross

It was finally time to deploy the gliders and I couldn’t be more excited! Autonomous vehicles are regarded as the future of oceanography, and I feel extremely lucky to be deploying these on my first scientific research cruise.

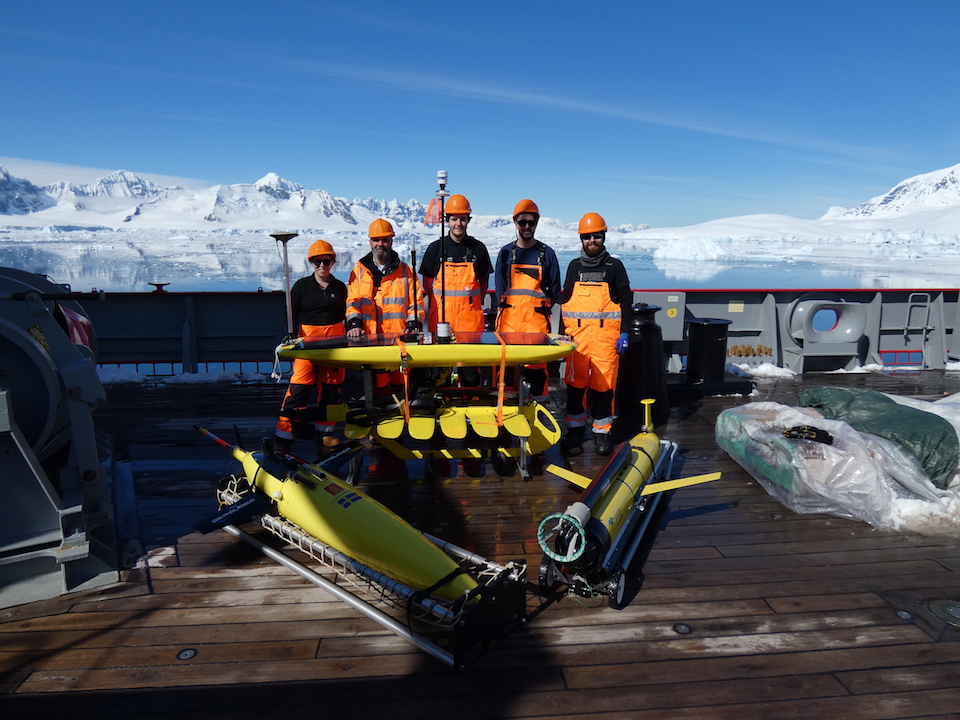

The ORCHESTRA underwater glider fleet is made up of 6 gliders (4 Slocum gliders, a Seaglider and a Wave Glider). This is the largest number of gliders to be deployed from the RRS James Clark Ross, so far.

The Slocum gliders and the Seaglider are both deep-diving underwater robots that move in a similar way through the water. Each time the gliders are at the sea surface they send their GPS location and the data they have collected during the dive to a computer.

We programmed the gliders with their new commands and then they were all set to dive underwater and continue their mission. To dive deep underwater the gliders deflate an air bladder, retract oil into an internal oil bladder (to make themselves denser), and move their battery towards their nose. As the glider start to sink, the wings propel it forward. The Slocum glider then steers using a rudder, whilst the Seaglider steers by rotating its battery. Both gliders can dive up to a depth of 1 km before they climb back to the surface, and transmit the data.

Gliders can be fitted with a range of different sensors. The standard sensors measure the pressure, temperature and salinity of the sea. In addition to this, the gliders I deployed were fitted with turbulence sensors that measure centimetre scale changes in temperature and velocity. Using these measurements, I can study how water and heat mixes in the ocean. This is important as these processes are responsible for melting ice shelves.

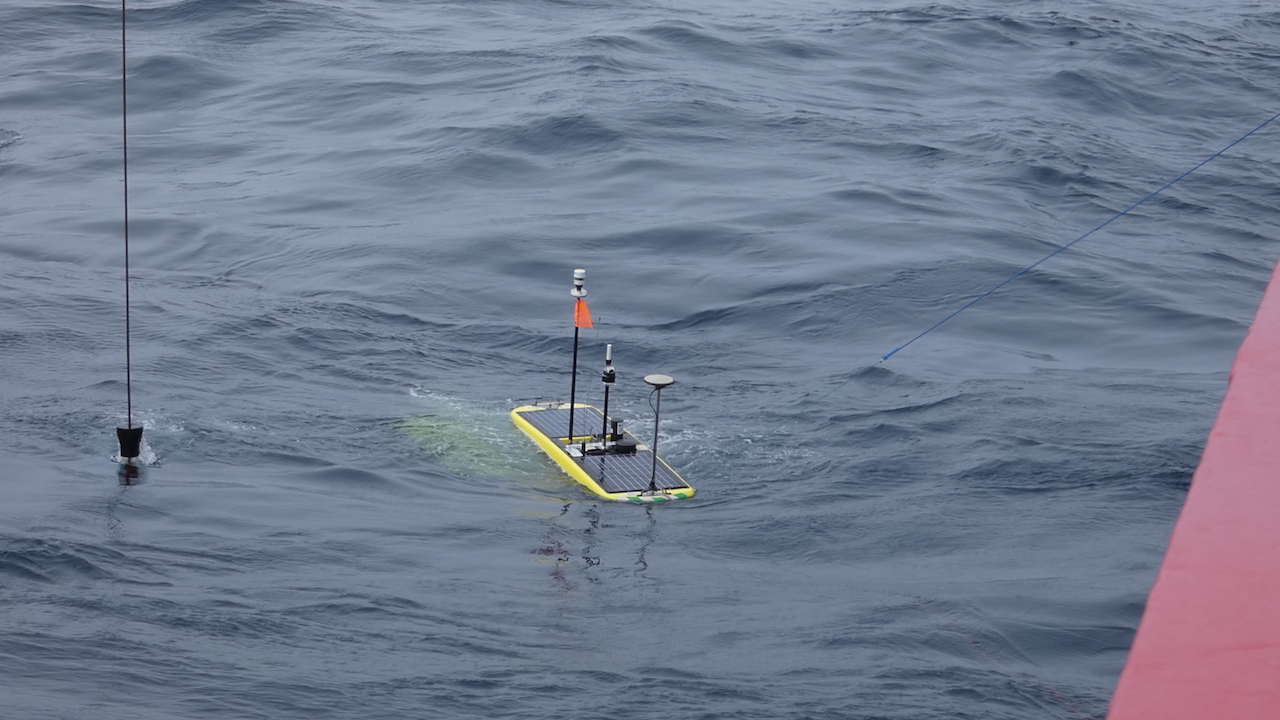

The Wave Glider works slightly differently, one half sits on the surface and the other sits underwater connected by a cable. The underwater part has wings that uses wave power to pull floats along. On board the float there are solar panels, a GPS, a time-lapse camera and sensors to measure the air temperature, pressure, wind speed and direction, as well as information about the water currents and wave heights.

All the gliders were deployed at the southern end of Drake Passage and will be left collecting data for 3 months! During this time, there will be several fly overs by MASIN, British Antarctic Survey’s atmospheric research aircraft, led by atmospheric scientists as part of the ORCHESTRA project. By doing this, we will be able to compare measurements to look at the transfer of heat between the ocean and the atmosphere, allowing us to see how the oceans are changing our climate.

See you in 3 months, gliders!