How to test a new polar ship

16 July, 2021 RRS Sir David Attenborough

At British Antarctic Survey, the next chapter in shipborne research is about to begin. Britain’s new polar ship, the RRS Sir David Attenborough, has been undergoing an intensive programme of tests and trials ahead of her maiden voyage to Antarctica later this year.

The Sir David Attenborough is an incredibly complex vessel. Its one-of-a-kind design had to fulfil a huge number of unique requirements and there are thousands of components to test.

But how do we do this? Where do you start testing a 15,000-tonne ship?

Well, preparation is key. A lot of tests and training – such as emergency exercises – can be done while the ship is in port. Once all these alongside tests are complete, the ship is taken to sea. The crew then start the safety critical operational tests, like anchoring, before working through all the other on-board systems one-by-one.

Where the ship is taken to do the at-sea tests depends on what we are planning to test; there are many factors to consider, including water depth, distance from land and other ships, and – most importantly – the weather! For example, some of our initial trials were done close to the Isle of Skye because it offered significant shelter for launching boats and practicing our man overboard recovery techniques.

Dr Pepijn Zoet, Director at PZ Dynamics, performed the analysis of the manoeuvring trials and shaft power measurements. He also performed the noise and vibration and underwater noise measurements and analysis on behalf of Lloyds Register Consulting, because of Covid-19 travel restrictions.

In this guest blog, he shares how you go about testing a new polar ship.

Manoeuvrability

Manoeuvrability is the ability of a ship to change its course – to move around an obstruction such as an iceberg for example.

For any ship to be commissioned, there are a standard set of manoeuvring trials which need to be carried out. These tests include:

- Speed trials (at three different power outputs)

- Turning circles

- Man-overboard tests (trying different ways of returning as efficiently as possible to a location where someone fell overboard)

- Zig-zag test

While the ship completes each of these tests, different measurements are taken and compared to regulatory or contractual requirements. These measurements include:

- Ship position, course and speed

- Wind speed and direction

- Ship rate of turn

- Rudder angles

- Propeller rotation speed, torque and power, and pitch

- Fuel consumption (the engine is trialled in different configurations to find what is the most fuel efficient over long distances.)

To make these measurements, GPS loggers are used to register the position of the ship every second during the test – this can then be used to plot the ship’s trajectory, speed and course.

So-called ‘strain gauges’ are fitted on to each propeller shaft – a nerve-racking job which requires precision! These gauges measure each shaft’s twist angle and transmit this information to a laptop, where the power that is being transmitted through the shafts to the propeller can be calculated. This information is also measured and calculated every second as the manoeuvring tests are carried out.

Power measurements are especially important for the speed test. There are three different operational conditions for which the speed needs to be tested and verified:

- Full power output

- 13 knots speed and required propeller shaft power and fuel consumption

- 11 knots speed and required propeller shaft power

As well as these standard manoeuvres, the crew also test emergency steering. It’s possible to steer the ship locally, from where the rudders enter the hull – but this takes a bit of practice! This gets tested and practiced when the ship is away from land and other ships, and means the crew are prepared for any issues with the steering.

Underwater noise

The ship needs to be as quiet as possible while underway to avoid negatively affecting marine wildlife and sensitive acoustic instruments can gather accurate scientific data.

During the design, a lot of care was given to reduce the transmission of structure-borne noise from machinery to the underwater environment. The engines have been designed to run as silently as possible, and special attention has been given to avoiding ‘sweep-down’ of bubbles around the hull that could interfere with acoustic sensors.

There are two ‘notations’ that need to be fulfilled – the DNV Silent(S) and Silent (R). Silent(R), or Research, is the most stringent of the two requirements.

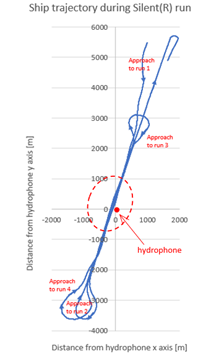

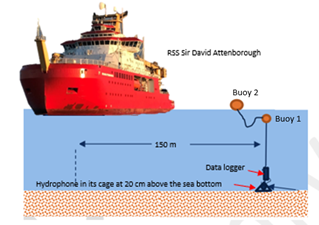

Underwater noise was tested using a hydrophone/buoy system. A hydrophone is placed in a cage on the seabed together with a data logger which continuously records the noise picked up from the hydrophone. Tests were carried out at night, from 1630 until 0200h. The ship performs ‘runs’ at various operational speeds, passing the hydrophone on both the starboard and port side.

The evaluation of the underwater noise signature requires extensive post-processing analysis of data. For example, the noise measured needs to be corrected for things like noise reflection phenomena and the distance between the ship and the hydrophone. After processing is complete, so-called noise spectra are generated, which show how noise energy is distributed over frequency.

The RRS Sir David Attenborough (SDA) is currently undergoing its next round of sea trials, an important part of the preparations for the ship’s first Antarctic mission. Find out more about the SDA’s next phase of sea trials here.