Exploring South Georgia’s seafloor fauna with SQUID

21 March, 2017

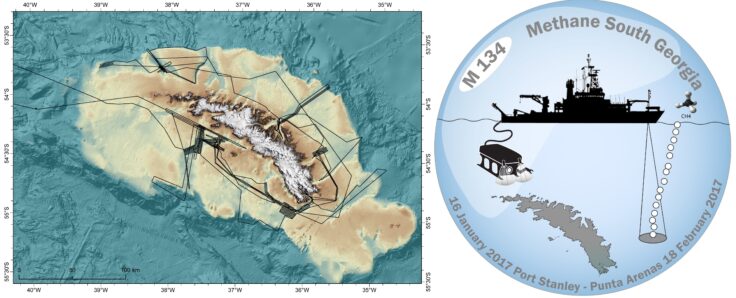

I recently spent four-and-a-bit weeks aboard the German blue water research ship RV Meteor along with Oli Hogg, my PhD student. We took part in the “Methane South Georgia” research cruise led by Professor Gerhard Bohrmann from MARUM (Center for Marine Environmental Sciences in Bremen).

We travelled to Stanley in the Falkland Islands in mid-January on a slightly convoluted series of flights via Santiago de Chile, Punta Arenas and Rio Gallegos (Argentina). After a brief visit to Gypsy Cove, just outside Stanley, to see the Magellanic penguins, we departed the Falklands on Meteor. Three days of sailing brought us to South Georgia, where we would be collecting our data.

The overall objective of the cruise was to investigate in detail the methane gas emissions that were discovered in the glacially carved valleys of South Georgia’s continental shelf in 2013. These methane emissions are caused by bacteria that live in and just beneath the seafloor and decompose dead organic matter. Specifically, the cruise addressed questions including the chemical composition of the emissions, whether they reach the atmosphere in significant quantities, and what ecological communities form around the locations where methane seeps out of the seafloor.

Oli and I were particularly interested in how these methane emissions affect seafloor biodiversity – whether the presence of methane means that the animals living on the seafloor are different from those elsewhere in South Georgia and the rest of the Southern Ocean.

We were also keen to collect data on the presence of microplastics, which are poorly studied in the Southern Ocean and tend to sink to the seafloor over time. The numerous sediment samples taken from areas around South Georgia on this research cruise will hopefully allow us to address both these questions.

Our main task on board was to work with the team controlling MARUM’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) called SQUID. The ROV travelled to the seafloor to investigate the amount of gas seeping out as well as its composition. The ROV also sends back a live video feed, which we used to investigate whether the animals living near the methane seeps were “typical South Georgians” or whether they were unique to the seepage sites.

Oli will also use the video footage from the SQUID ROV to check the accuracy of his habitat-mapping models, which will be used in the revision and assessment of the Marine Protected Area around South Georgia which was designated in 2012.

I also gained an unexpected new source of data from the multi-corer, a device that is lowered from the ship and returns a number of samples from the seafloor. The multi-corer can return up to 12 samples on each deployment, but the biogeochemists on board only needed a few of these – which left us with several tubes of seafloor material to sample, sieve and fix in search of seabed-dwelling organisms.

We have returned home with a range of exciting new datasets which we look forward to analysing. For example, we have unique sample set for macro- and meiofauna (animals bigger than 0.05mm, or the width of a human hair). Using this information, we hope to understand how methane in seafloor sediments influence the faunal biodiversity and abundance.

We have also obtained datasets on the presence of microplastics at different sites off South Georgia, which exhibit different levels of human impact. Finally, besides the video footage from the ROV, Oli is writing up our findings about some of the amazing hard-rock animal communities we encountered on the ocean floor.

We look forward analysing the many datasets we have collected and would like to thank the MARUM team for a highly productive and enjoyable science cruise!