ANTARCTIC BLOG: Science from the air #5

26 January, 2016 Rothera

Wrapping up

I have started several of my blog posts saying I am writing in various odd/unusual/uncomfortable locations…the back of a Twin Otter, or in a mountain tent high on the Antarctic Plateau. This time, however, I am sitting in a New Zealand hotel lobby, drinking a flat white, and Antarctica seems a different world.

My journey from Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station (Pole for short) to here has taken me thousands of kilometres, and a temperature change of about 50 degrees, but my journey out (from one flat white to another) could not begin until the PolarGAP survey was complete.

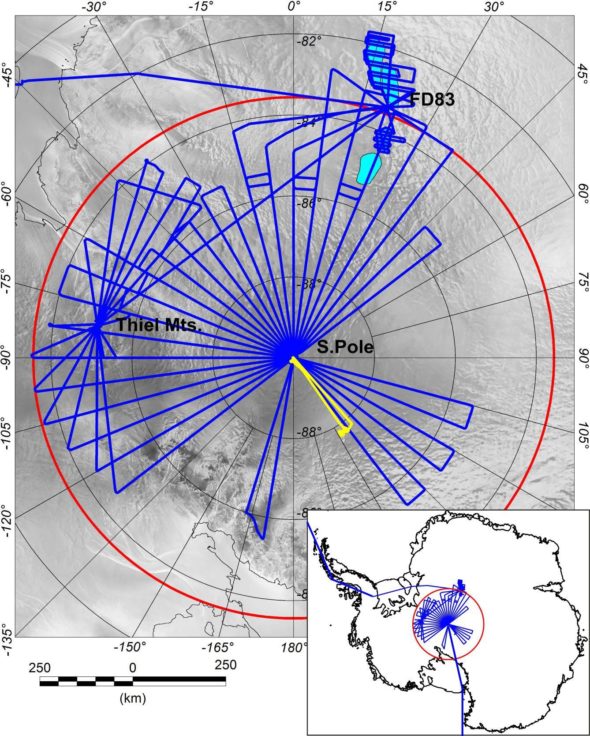

Once we were settled in at Pole our days fell into a regular routine. Up at 6, breakfast, then a check with the meteorological team of the most recent satellite images and weather forecasts for the day. Then it was a chance to consult the master plan, the map carried from tent to tent with lines gradually filled in as the survey progressed. From this plan we decided which flights were the priority and which could be done given the weather. After this it would be about two hours before the survey aircraft was ready to depart on her first flight of the day. Four and a half hours later the survey aircraft would return, re-fuel, and after a change of pilot and operator was ready to go again for a second flight of the day.

Many of the survey flights headed out over the featureless flat white Antarctic Plateau, but some flew towards the spectacular Transantarctic Mountain range. This range is over 1500 km long and acts as a barrier between the high East Antarctic ice cap, and the lower lying West Antarctic ice sheet, floating Ross Ice Shelf, and Ross Sea. Geologically speaking these mountains are unusual, whereas other continental scale mountain ranges like the Alps or the Himalayas are created where tectonic plates collide, deforming and pushing up the rocks, the Transantarctic Mountain formed along the margins of a rift. This means that flat lying sediments deposited close to sea level are now seen thousands of meters up in the mountains.

With peaks rising well over 4000 m in places the flights towards the Transantarctic Mountains could only be contemplated when there were no clouds on the satellite pictures. Even given this precaution one of our flights had to be cut a little short given the extreme downdraughts across the mountain front, where the cold air of the Antarctic plateau falls down towards the Ross Sea, potentially at a rate faster than the survey aircraft can climb.

As the PolarGAP survey progressed the master map rapidly filled in until, after a brief weather delay, we had one single flight remaining. However, this flight was to test a model of the shallow snow and ice layers produced to explain apparent differences in satellite observations. To do this a completely different radar system was required, and the gravity sensors needed to be removed so the survey aircraft would be light enough to operate. We therefore spent an entire morning patiently removing the radar system and gravity meter from the survey aircraft and packing it neatly away. The afternoon was then spent installing the so-called ASIRAS radar, which simulates the radar system on the satellite which had revealed the unusual anomalies around the South Pole. The final ASIRAS flight went well, with around 30 Gb of data collected. However, it will take months of post processing and analysis to determine if the original hypothesis is correct, or if a new explanation for the variation in the satellite data is required.

After the ASIRAS flight the South Pole management team requested that for our very final flight we flew a photographer over the station. This was a great opportunity for the South Pole management to get new images of the station and to understand the layout of the cargo and snow banks around the station. At the same time the multiple over-flights of the station will help calibration of the PolarGAP laser data, as specific features on the station building can be seen, and were independently mapped using GPS placed on the roof. It was also a great opportunity for me to see the station from a completely new angle.

After our final flight it seemed only right that, like the teams of skiers and other expeditions, we had our final team photo in front of the ceremonial South Pole. In addition, as an essential part of our team, VP-FBL our survey aircraft also got to have her polar photo shoot.

Finally, six weeks after heading into the field from Rothera Research Station VP-FBL was ready to depart from Pole Station for the two day journey back to Rothera, and the next survey. At around eight in the morning Ian, Andy, Carl and Mike pilled on board with all their kit. I stood and watched the engines start up, and once they were running disconnected the ground power leads for the final time. It was a moment of mixed emotion for me – we had just completed an ambitious and challenging project in one of the most remote locations on Earth, finishing almost a week early; a great success. At the same time my friends and colleagues who I had worked so closely with over the last few weeks were departing for a new adventure, leaving me standing alone amongst the cargo lines at South Pole.

After VP-FBL departed for Rothera all that remained was for me and Rene, one of the project Principle Investigators from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), to return home. This could have been hampered by the traditional Antarctic weather delays, and many people at Pole had been waiting almost a week to get out. However, the day after VP-FBL departed the weather came good and a US ski equipped C130 Hercules was able to fly in, and there was room on board for us all. With temperatures hovering around -30C the aim was for a quick turn around, and soon after the C130 arrived we were all boarding for the flight down to McMurdo, the largest of all the Antarctic stations, located on Ross Island at the inland end of the Ross Sea. On the way down we had to cross the Transantarctic Mountains one final time, with spectacular views of the mountains and glaciers which carve through them.

On arrival at McMurdo there was a definite sense of being in a very different place. The air literally felt thicker after the high altitude and extreme dryness of South Pole. The temperature, even though we arrived at midnight, was hovering around zero. This dramatic change meant that a fleece and thermal was all you needed to be outside, rather than five layers of extreme cold weather clothing, which was a great relief. Another change I noticed was in how you interacted with the people. At Pole you would say ‘Hi’ to everyone you met in the corridor, irrespective of if you knew them or not. McMurdo is much more like any other town where is normal to just walk past someone unless you know them.

After a night at McMurdo, and taking the final gravity measurement to tie the PolarGAP survey into the global gravity field we were straight back onto a C130 for the long flight north to New Zealand. This eight our flight was a bit of a test of endurance. There was little sound proofing compared to a commercial aircraft, so earplugs were needed the whole way, and any conversation with the person next to you had to be shouted, so most people read, or tried to sleep away the hours until we arrived in New Zealand. On arrival in New Zealand I had completed a total traverse of the Antarctic continent, from Peninsula, to Pole and beyond.

This will be my final blog post on the PolarGAP project. It has been a great adventure, and a great success. This is thanks to the great team of people I have been working with, and all those on the stations, field camps and back in the home offices of the various institutions involved. Together we have been able to achieve a really remarkable feet, carrying out a reconnaissance survey of one of the most inaccessible places on earth, and finally filling the PolarGAP. Much work remains to be done to turn our raw data into a final interpreted product. Even then, many questions will remain about the nature of the Antarctic continent, which remains one of the most mysterious, least understood and fascinating places on our planet.

Tom Jordan is part of the PolarGAP project, an ambitious international collaboration which will use airborne geophysics to explore one of the last known frontiers on our planet – the region around the South Pole. For more information see the project page.