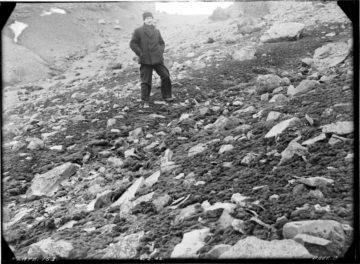

Scientific research formed a key component of Operation Tabarin. Despite the exigencies of the Second World War, expedition commander James Marr, himself a trained zoologist, was able to assemble a range of scientists and specialists to join his team.

The first cohort arriving in 1944 included botanist Ivan Lamb, meteorologist, Gordon Howkins, geologist William Flett and surveyor Andrew Taylor. They were joined in 1945 by zoologists Gordon Lockley and Norman Marshall, surveyors David James and Victor Russell and meteorologist Alan Reece.

A variety of scientific work was carried out at all the bases, but particular emphasis was given to biological work at Base A; to geology, glaciology and meteorology at Base B; and to geology, topographical survey and biology at Base D.

The research undertaken during Tabarin was an important beginning and laid the foundations for the more complex research of later decades, particularly in the spheres of topographic survey, geology, glaciology, meteorology.

Ivan Lamb, the expedition botanist, was fascinated by the region’s varied and resilient lichens. His enthusiasm carried over to other members of Operation Tabarin as medical officer Eric Back recalls:

Lamb’s accomplishments were summarised in his final general botanical report written in January 1946:

“During the period of our stay in the Dependencies, from 4. February 1944 to 16. January 1946, a total of 1030 selected botanical specimens h[ave] been collected. These include lichens, bryophytes, algae, phanerogams, fungi, and diatoms, the number in each category as follows:

Lichens…. 865

Bryophytes…. 84

Algae, marine…. 40

Algae, freshwater and terrestrial…. 17

Phanerogams (grasses)…. 5

Fungi (lichen parasites)…. 7

Diatoms, marine…. 10

Diatoms, freshwater…. 2

Total…. 1030

…

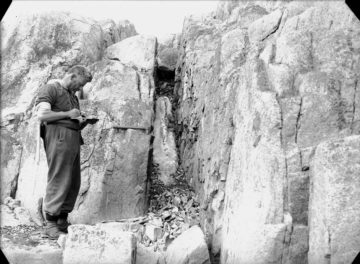

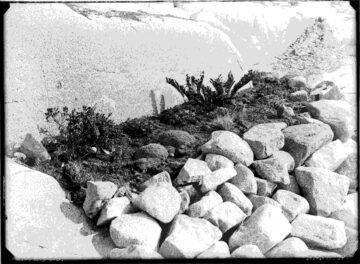

The greater part of the collections were made around our two bases at Port Lockroy (Weincke Island), 1944 and Hope Bay, 1945, but a considerable amount of material was also acquired on local excursions from these bases and notably on the three sledge journeys, covering in all a distance of about 800 miles, in which I had the privilege of taking part.…

All lichen specimens were determined as to their genus; this entailed the use of the microscope with most of the crustaceous species. Some of the genera, and in one case an entire family, had not been previously recorded from the Antarctic; others were new to the Graham Land region…

The number of species new to science cannot be indicated until the taxonomic study of the material, which I hope soon to undertake at the British Museum (Natural History), had been completed; my impression at present is that some twenty or thirty species, perhaps more, are new.”

Source: Ivan M. Lamb. (Archives ref: AD6/1/1945/N)

Read Lamb’s full botanical report here.

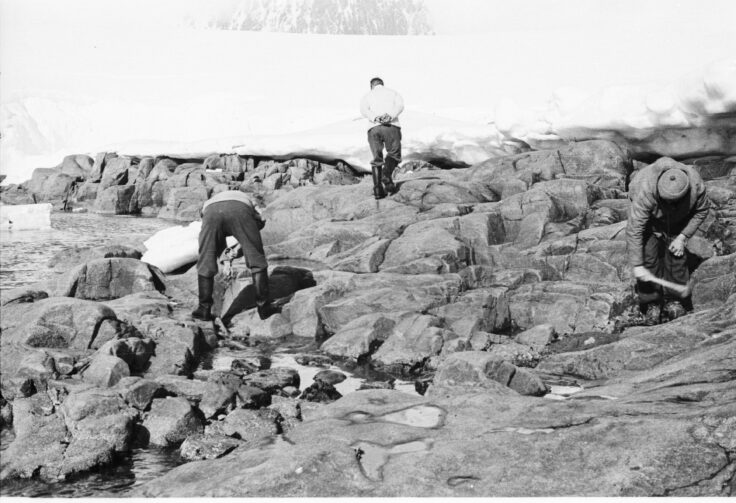

Extensive geological work and specimen collection was also carried out under the direction of geologist William Flett:

“A most comprehensive collection of palaeobotanical specimens has been made, the great majority of the most striking samples having been collected by L. Ashton, both from scree slopes and in situ. They comprise well over 600 numbered specimens and a large number of uncatalogued specimens. …

Taylor, Lamb, Russell and Davies formed the party for the second sledging trip between 9th. November and 29th. December 1945 and covered over 500 miles. They brought back an extremely large collection of diversified types of igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks and a very great number of fossils.”

Source William Flett. (Archives ref: AD6/1D/1945/G)

A core objective of the field parties operating out of Port Lockroy in 1944 and Hope Bay in 1945 was to collect survey data in order to create new local maps or to improve upon existing ones. Two additional surveyors, David James and Victor Russell arrived in early 1945 to assist Andrew Taylor at the new base established at Hope Bay. Taylor describes the mentality of a surveyor and the challenges of carrying out this work in difficult conditions:

Port Lockroy was the site of early hydroponic experiments in 1945. Base commander Gordon Lockley explained the limitations of the work:

“Some attempts were made at growing vegetables in culture solutions (“hydroponics”). In general these experiments were a failure as it was not possible to provide the necessary heat and light requirements. If a heated greenhouse were available vegetables could doubtless be grown in the Antarctic by this method whose chief advantage would appear to be the small space which would be required to ship the necessary chemicals as opposed to a shipment of soil.

Several crops of mustard and cress were successfully raised during the winter in shallow boxes of earth. Crops of mustard and cress and radishes which were planted in the open in guano beds at Goudier I., Port Lockroy in early Jan. were growing well at the time we left the base. Some Chinese Cabbage seeds, planted in Feb. last, had sprouted this Jan. and were in the cotyledon stage on Jan. 15th. Experiments were necessarily conducted with the few seeds available which had been supplied by the Director of Agriculture, Falkland Is. It is suggested that it might be possible to raise certain plants in the open during the Antarctic summer if seed etc. were carefully selected with this end in view. The chief requirements would appear to be rapid development, resistance to low temperatures and to sudden temperature changes and shallow rooting.”

Source: Gordon Lockley. (Archives ref: AD6/1A/1945/A)

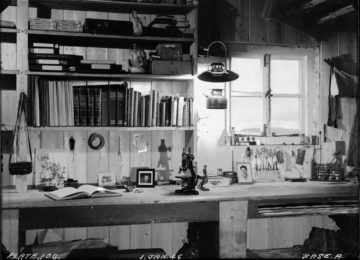

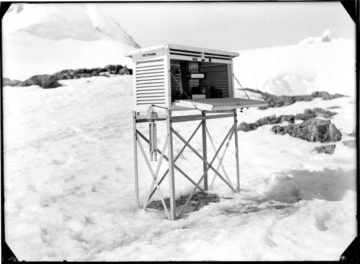

Gordon Howkins was as the expedition’s chief meteorologist from 1944 to early 1945. He served on Deception Island and recalls the met work conducted there and the challenge of waking up at regular intervals to take observations:

Though primarily acting as expedition doctor, Eric Back also doubled as meteorologist at Port Lockroy and later at Hope Bay. He too experienced difficulties in keeping time:

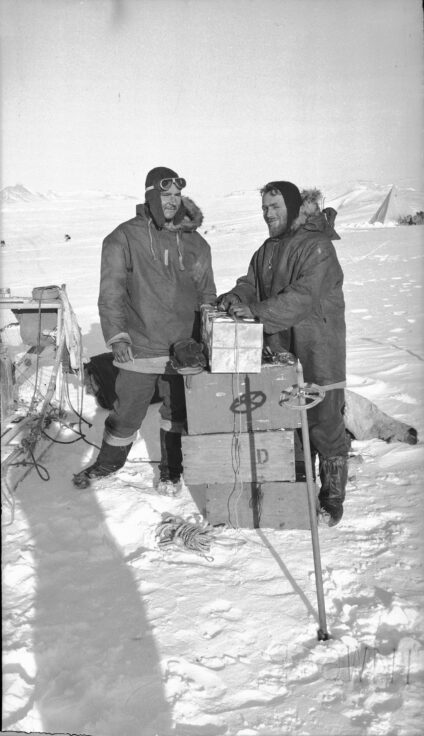

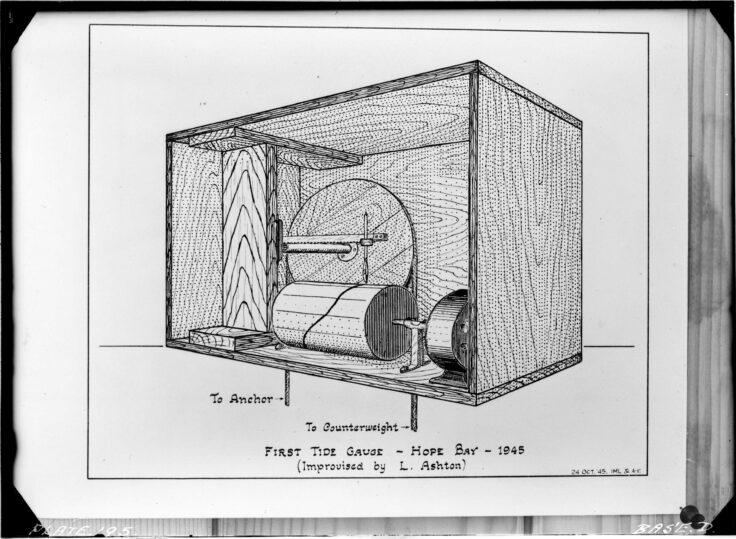

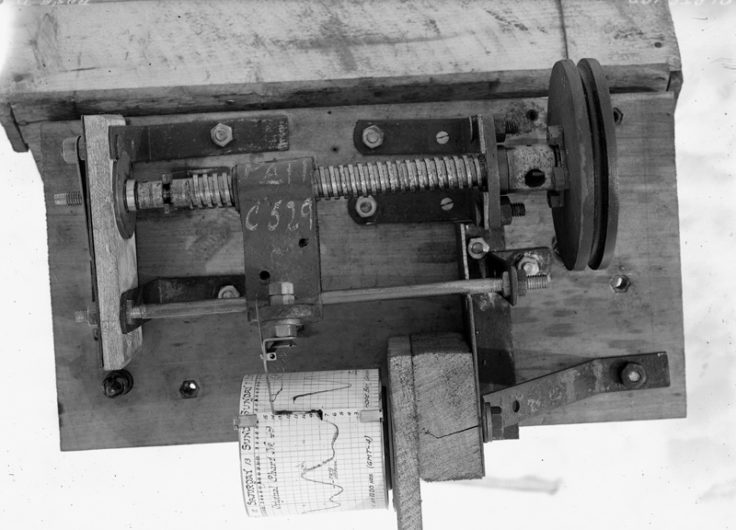

Expedition carpenter Lewis Ashton (known as “Chippy” as befitting his profession) was also called upon to construct a tool for measuring tidal movement. Taylor explains:

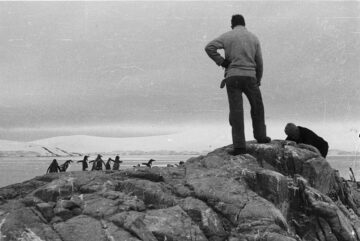

Ornithological observations were also made around the bases. The following is an excerpt from a natural history report for Hope Bay written by zoologist Norman Marshall – it covers, among other subjects, the movements of local penguins:

“Adélie – Pucheramphus adéliae.

The penguin population of the area is predominantly composed of this species. When we arrived at Hope Bay on Feb 12. thousands of these penguins were seen lining the eastern shores of the bay while many others were “seen porpoising” and fishing in the sea. The rookeries extend along these shores almost to the site of the D. hut, the populations being densest around Eagle Cove and Seal Point. The adults were observed feeding the young with krill. Many of the young did not seem to have learnt the art of “toboganning” for their elders were able to outdistance them by this means when being chased for food.

On Feb 20 the adelies began to leave the area and so rapid was the migration that by Feb 26 only a few of the young remained. The latter are presumably late broods of chicks who have not yet learned to swim and catch food for themselves.

The last record to be noted of an Adelie was on April 8 when three were seen close to the Stone Hut.”

Source: Norman Marshall. (Archives ref: AD6/1D/1945/N2)