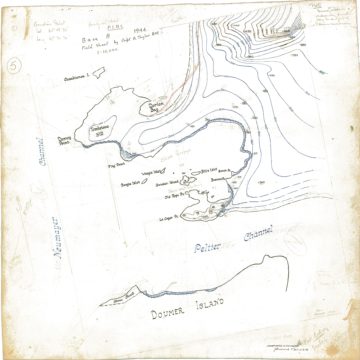

With the completion of Bransfield House at Port Lockroy in April 1944, the commander of Operation Tabarin, James Marr, began to plan the expedition’s first major sledging trip, a survey journey to nearby Wiencke Island. Marr would lead the field team comprising of stores officer Gwion Davies, surveyor Andrew Taylor and botanist Ivan Lamb. Their aim was to gather survey data for mapping, collect geological and botanical specimens and, of equal importance, to test their sledging and scientific equipment in the field. Lacking dogs, the team’s two Nansen sledges, each loaded with 700lbs of food and equipment, were hauled by hand.

Stores officer Gwion Davies spent much of the dark Antarctic winter preparing for the trip:

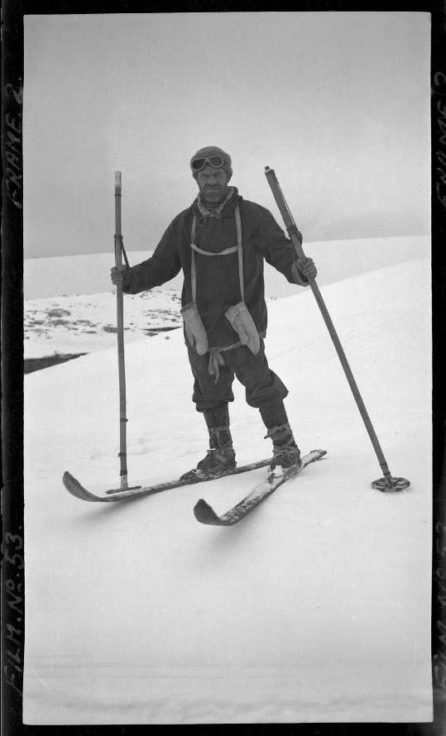

The men also had to learn to ski, as Davies describes:

Just getting to the starting point for their journey, the interior of Wiencke Island, proved challenging according to Marr:

“Monday, 18th September

Final details of preparation being completed, the survey party, consisting of Taylor, Davies, Lamb and myself, set out after lunch with two 12-foot Nansen sledges, Davies and I pulling one sledge, Taylor and Lamb the other. The latter was the survey sledge with the sledge meter Ashton made out of an ordinary bicycle wheel and an old Cherub log I got from Number One of the “Scoresby”. …

The crossing of the quarter mile or so of flat sea ice separating our small islet from Wiencke Island was easy in spite of the loads we were dragging-nearly 700 pounds a sledge. The ascent of the steep ground of the large Gentoo rookery which occupies the southern horn of the harbour was a different matter. Both sledges stuck immediately we attempted the gradient and the party had to double up and relay the loads. …

Leading up from the summit of the rookery, about a hundred feet up, and connecting it with the glacier above, is a steep knife-edged snow ridge, 40 feet high on the harbour side and dropping sheer away for a 150 feet or so into the Peltier Channel on the other. The condition of the surface varies greatly. Sometimes, especially after a heavy fall of snow, it can be climbed on a zig-zag traverse of skis. At other times steps have to be kicked or cut.

At the bottom of the ridge the sledges were off-loaded and the gear carried piecemeal up the slope and along the knife-edge to the glacier above. The empty sledges were then hauled up, reloaded, and left in shallow trenches for the night. We returned to the Base in time for dinner.”

Further excerpts from Marr’s travel account of the journey provide an insight into the daily life and difficult conditions the party encountered:

“Friday, 22nd September …

Shortly after mid-day halt we entered the mouth of the Luigi Glacier. My sledge was astern and slightly to the right of the other while negotiating a traverse on a steep snow and ice slope below wall mountain it suddenly broke through a snow bridge and tilting sharply over stuck in the mouth of a deep and narrow crevasse. The Doctor who was shoving behind narrowly escaped going down. This was an unpleasant surprise especially as the surface over which we were travelling appeared to be perfectly sound and without the faintest trace of crevassing. On closer inspection the crevasse was seen to run far ahead directly in the line of the path that Davies and I had been travelling. Had the snow bridge broken away farther than it did both sledge and sledge party must have gone down.

An attempt to haul the sledge obliquely out of the crevasse with the Alpine rope attached to the main trace ended in our carrying away the cow catcher. Whereupon I off-loaded the sledge on a bowline at the end of the rope, passing the gear back to Taylor and Lamb while Davies, Ashton and the Doctor anchored the other end of the rope paying out slack as required. The empty sledge was easily lifted out of the mouth of the crevasse.

It was now about four o’clock in the afternoon and the Doctor and Ashton left us and skied back to the Base. I repaired the broken cow catcher as best I could while Davies reloaded the sledge. Both sledges now began the stiff ascent of the glacier, a slow and arduous business which got slower and slower as the gradient began to tell. We had travelled little more than 300 yards with many halts to rest when it became clear that we should get nowhere that night unless we again doubled up and relayed the loads. Davies and I accordingly abandoned our sledge, which had most of the camping gear including our two tents, joined Taylor and Lamb and together set off up the glacier, at first at a somewhat better pace. It was still however exhausting work and in our anxiety to find the easiest route and at the same time avoid a sharp dip in the glacier which was probably a wide filled-in crevasse we approached rather more closely to the sheer north or Wall Mountain side than I cared for. This was very nearly our undoing. Suddenly, as we were edging out into the middle of the glacier again, we heard to our left and directly above us a deafening roar like the crackling of continuous thunder and glancing up saw hundreds of feet above a great mass of ice break away and come hurtling down on us. We stopped in our tracks, I for one [was] momentarily struck useless with terror and a sense of complete helplessness. Even as we hesitated the avalanche had reached the glacier and was now churning up before it a dense white cloud of powdered snow which rolled towards us with the speed of an express train. With one accord we turned and ran obliquely down the slope away from the approaching danger to be brought up instantly by our harness when we threw ourselves flat on our stomachs hands over heads (instinctively I think) in the forlorn effort to protect them. We had scarcely got into this position when we were assailed by a tremendous wind and immediately afterwards were enveloped in the whirling snow cloud so dense that it blotted out the light. I remember clearly that in that instant my fear went away and the only thought that passed through my mind was that in a second or two I should receive a crack on the head that would finish me. It was all over in a second or two. The rush of air ceased, the roaring died away, light returned through the thinning snow cloud and we got to our feet very shaken but undamaged. The avalanche had evidently just failed to reach us. How close it had got we did not know. There was still a good deal of whirling snow about and in any case we did not stop to look but dashed back to the sledge and started off up the slope as hard as we could go.

Wednesday to Friday, 27th to 29th September

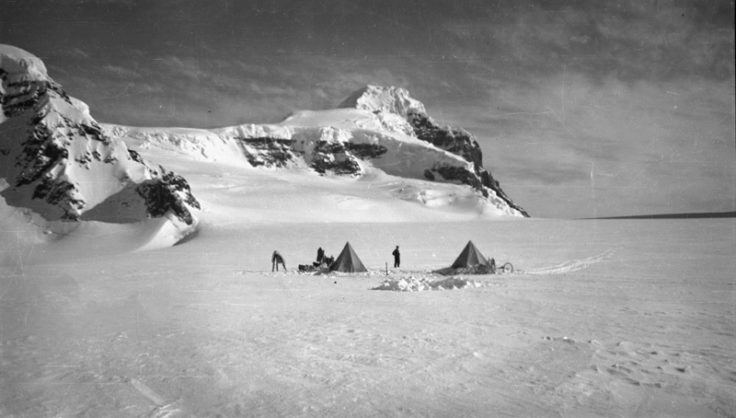

Westerly gales, blizzard and fog. Confined most of the time to our sleeping bags. During the night of Friday the gale reached a pitch of violence that made me wonder if the tents would hold. We had not bargained for such weather. Food lasting out as foreseen but paraffin getting low. Will have to go back to the depot for more as soon as weather permits.

Saturday, 7th October

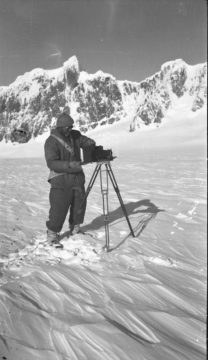

Fine and clear with stiff northeasterly breeze. Taylor, Davies and I left with the survey sledge after breakfast to continue the survey to the north. We occupied a station about a mile to the north of the camp on an ice-slope more than half-way up a 1200-foot peak crowned by a great cornice shaped like a gigantic parrot’s beak. The day was spent around here, Taylor busy with theodolite, rangefinder, plane table and survey camera. Davies and I recorded or worked the rangefinder for him- cold and trying work in the bitter wind. Lamb remained quietly in camp. He has blisters on his feet but is able to get about in duffel slippers and sealskin boots. …”

Read Marr’s full travel report here. Lamb’s account of the sledging trip can be found here.

On the 10th October, as the survey party neared the depot at the start of the route, Marr picked up a signal from the Governor of the Falkland Islands requesting an urgent reply. Marr skied back to Port Lockroy and sent John Blyth to take his place with the field party.

He subsequently travelled aboard the Scoresby back to the Falklands to discuss plans for the second year of Operation Tabarin with Governor Sir Allan Wolsey Cardinall.

Compared with later sledge journeys, the distance covered and time in the field away from base (24 days) was modest. Work was also hampered by bad weather throughout the trip. Survey work could be undertaken on only 12 days. Despite this, the journey’s objectives were largely met, with a number of botanical specimens collected and Wiencke Island, in the main, successfully surveyed. More importantly, the men involved had grown accustomed to living and working in the field.

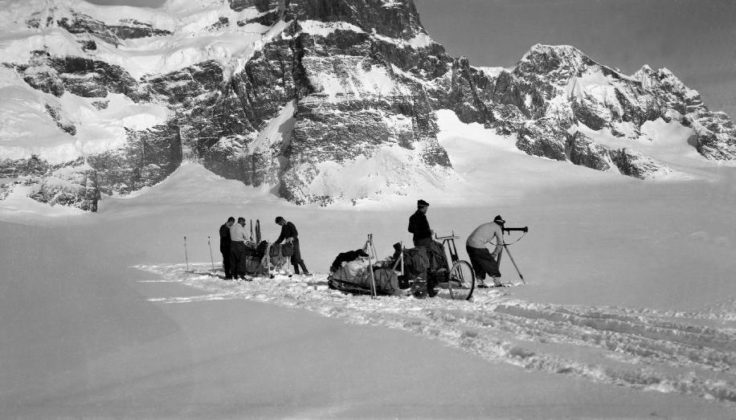

Lunchtime halt at base of Wall Range, Sep 1944. (Photographer J. Marr. Archives ref: AD6/19/1/42/7)